Recently, I had the privilege of meeting local author Judi Merriam...

I’m always inspired by fellow writers, and I have deep respect for those who walk through tragedy and deep grief and rise again.

Judi Merriam is one such person. After her son, Jenson, took his own life at 18, her path through profound sadness and guilt allowed her to develop empathy for those who grieve and gave her unique insight into how to help others who walk this often lonely road.

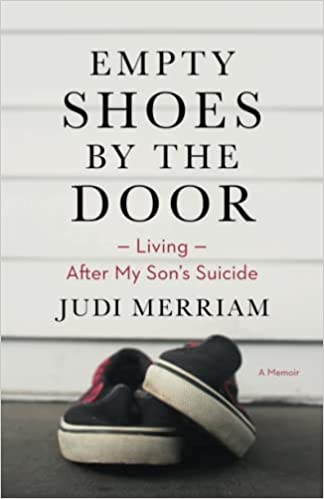

In her new memoir, Empty Shoes By the Door, Judi tells the story of her beautiful son’s life, his death that blindsided all who knew him, and the lessons she’s learned on the difficult journey from then till now.

I recently had the opportunity to talk with Judi at length and read her beautiful words. Her love for Jenson, her husband, and their other two children is evident, and her spirit shines through, as you will see in the excerpts below.

Empty Shoes By the Door was released on May 16, 2022, and is available wherever books are sold.

From Empty Shoes By the Door:

I believe truth is typically the best course, so I follow Brene Brown’s advice and “rumble” with it regularly not wanting deception to claim victory. I’m convinced the only healthy way to deal with the factuality of a suicide is to meet it face to face from the heart wrenching moment it happens and not redefine it into something more acceptable. We also need to personally dictate how we’ll deal with it so as to avoid any delusion that would capture our thoughts and change it into something it isn’t. It’s impossible to dress up a suicide death and be truthful about it at the same time! Some try, but I don’t believe them.

I desire the truth of my own brokenness and survival shine a light on your personal path of grief if you need a pinpoint upon which to fix your eyes and gain encouragement. And I hope this glimpse of one of my fine children allows you a small understanding of what this world lost the day Jenson died, as in the words of Charles Dickens:

“And can it be, in a world so full and busy, the loss of one creature makes a void so wide and deep that nothing but the width and depth of eternity can fill it up?”

***

At age twelve, Jenson was in his first production of the teen musicals I directed for twenty-two years. This musical was “Anne of Green Gables,” and he played one of the youngsters/school children in the show. At one point, the school students put on an historical tableau of life on Prince Edward Island – a show within the show. In this scene Jenson entered the stage as the required mountain of snow, regaled in a full length white crinoline tied around his neck and hanging down to his ankles.

Unexpectedly, that mountain of snow stole the audience’s attention from the moment it stepped out from behind the back curtain. I should have warned the character who was speaking to wait for laughter at this point, but who would have expected such amusement from those watching. The mountain of snow took full advantage of the spotlight, and the face protruding above the crinoline lit up with delight at having captured the moment. By the sparkle in the eyes, it was obvious the wheels were turning as to how to milk this scene for all it was worth

Applause began to ripple through the audience encouraging more movement from the crinoline as it effortlessly swooshed downstage, spun around, and moved to its onstage spot amongst the rest of the cast. The original blocking was simple – walk on and move to your spot. However, that mountain of snow realized he had stolen the scene and seized the opportunity to command the stage. How could I reprimand the crinoline wearer after the show? Comedy had staked its claim in a mountain of snow.

Two years later, at age fourteen, Jenson would go on to play Pig Pen in “Snoopy, the Musical.” He was adamant he didn’t want to do any solo singing, only spoken lines. But in one of the songs, it was a perfect spot for Pig Pen to sing by himself in a large group number. However, “I don’t want to sing a solo,” was reiterated even more vehemently than the first couple of times it was uttered.

The choreographer, not the director-mother, finally talked Pig Pen into doing the solo with a lampshade on his head, since the line was about wearing said lampshade. This, of course, would be funny, and anything that brought laughter was agreeable to Jenson. A compromise was struck, and his voice loudly emanated from inside the lamp shade while Pig Pen took center stage.

Jenson loved laughter and making people cackle with joviality. He was quick witted and bilingual in both humor and sarcasm. They were almost his first languages and flowed from his creativity with fluency and ease. He also responded with delight and greater gusto when he made people laugh, whether on stage in his teens or in his film and writing projects. Almost all of his animation was created to be funny. Comedy appeared to be his love language.

***

It might be very encouraging if I could tell you that the over one thousand people who attended [Jenson’s] service are still a loving, supportive and caring network in our lives, but that’s not true, nor do I want it to be. It would be overwhelming to regularly interact with that number of people, so this is not a criticism of anyone. I will always be extremely grateful for those who gave us the gift of their time and support that day. I don’t, at all, wish to diminish the presence of any who loved us enough to show up two weeks after Jenson’s suicide.

I doubt many had ever been to a memorial service for someone who died by their own hand before that. It was probably very difficult for much of the crowd who came, and I’m honored they made the choice to do so. I have no desire to lessen anyone’s love for us or legacy of pain at Jenson’s loss no matter where they scattered to after January 7, 2012.

I assume most moved on with their own lives after they’d spent their personally perceived sufficient amount of time grieving for and with us. Since, as Jason Gray states, “trouble always draws a crowd,” several moved on to the next crisis that arose after Jenson’s suicide. Many stepped out of our lives for good, and because silence is almost always misinterpreted, their withdrawal from our contact was easier for both them and us.

These are neither judgmental nor critical statements but merely observations of people in general. Humans often have a short attention span when it comes to the bereavement of others; it simply seems to be our nature to not sit well with sorrow for long periods of time. Callousness is not my intention with this statement, just my conclusion since December of 2011.

Before Jenson died I most likely moved on quickly, too, especially when someone appeared better than they may actually have been. But now I understood what Jill Kelly so aptly describes with her words of, “a relentless, hollow ache echoes through every part of my broken life, and it will until heaven…a gaping hole once filled with joy is now empty.”

I now know that emptiness doesn’t end.