It's been a while since I've had something to say...

though I’m guessing my husband, Kevin, might disagree. 😉

What I really mean is that I’ve felt more of a turning inward lately. In these last weeks of winter, I took a bit of a social media break and have spent a little less time writing, a little more time reading. I like to think of reading as part research, part fueling. It takes my mind to places I might not have explored otherwise, allows me to consider new perspectives, and often unearths things I’ve kept long buried. As a writer, I sometimes force myself to step back from analyzing how an author has constructed a story–what it is that makes it so compelling, the small things that take it from good to great–and focus on the message the story itself has for me.

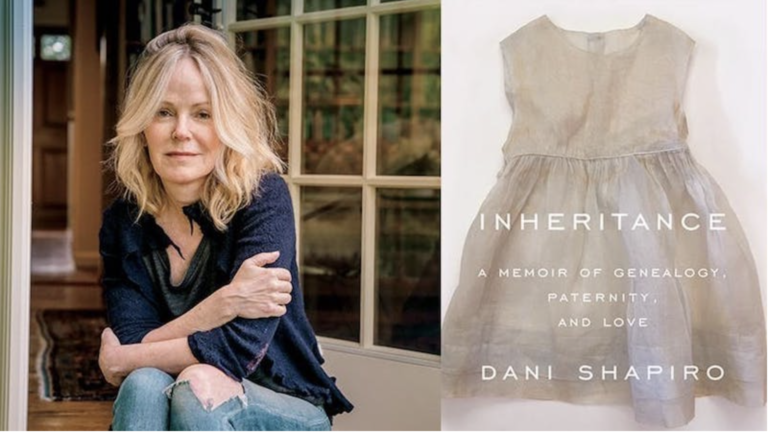

Yesterday I began reading Dani Shapiro‘s Inheritance. Today, my Kindle tells me I’m at 64%. I obviously haven’t been able to put this book down for long for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the author’s skillful writing.

From her website:

“In the spring of 2016, through a genealogy website to which she had whimsically submitted her DNA for analysis, Dani Shapiro received the stunning news that her father was not her biological father. She woke up one morning and her entire history–the life she had lived–crumbled beneath her.”

Within these pages, as Dani grapples with the this shocking news, she quotes Bessel van der Kolk, author of The Body Keeps the Score.

“The nature of trauma is that you have no recollection of it as a story. The nature of traumatic experience is that the brain doesn’t allow a story to be created.”

Her reflection on this quote: “I struggled to access any of my childhood or even my teenage years. I had no recollection of it as a story. And so I followed my own line of words to see where it would lead me…only in a state of half dreaming could I begin–and then only barely–to touch the truth.”

The best writing is both specific and universal. In an odd dichotomy, the more specific the stories we tell, the more others relate to them. In this case, though I hadn’t had the same experience as the author, her description of this sense of not having been part of one’s own childhood and later, of feeling “othered,” set off sparks of recognition for me.

I know these feelings well. In my teens and twenties, after my parents died, I coped by pushing forward. Better not to think too much about the life I’d left behind; better to double down on my determination to make a life for myself without a family behind me. It became more and more difficult to remember my parents, devoted as I was to looking ahead, not back.

But as I left them in the rearview, I left other things too. The sense of myself as someone’s daughter, the apple of someone’s eye, the notion that I was unconditionally loved and safe and supported.

At the same time, there was a feeling of “otherness.”

“I may look like you, but you have no idea who I am,” is a line that began playing in my mind back then.

At times it still does.

But here's the good news.

As Van der Kolk tells us, there are several essential steps to healing trauma, including reintegrating memories and changing their meaning. In the latter, “protagonists became like the directors of their own play, enlisting others to provide the love, support, and protection that had been lacking at those critical moments.”

An effective summary of the points in this landmark book can be found here.

“Trauma robs people of self-leadership – the feeling that you are in charge of yourself,” he advises. “A challenge of recovery is reestablishing ownership of your body and mind.” One of the ways this can be accomplished is through “finding a way to be fully alive in the present and engaged with the people around you.”

For me, the reclaiming of myself as someone who is worthy of love has been a lifelong process. This reconnecting with myself as the little girl who was, indeed, the apple of someone’s eye, has allowed me to let go of that sense of otherness. Others may not be able to inhabit the exact trauma that defined me, yet who among us hasn’t had trauma of one sort or another?

As a wise man once told me, “One person’s suffering isn’t lessened by comparing it to another’s.” In other words, I may have lost my family when I was young–and later my son–but that doesn’t make someone else’s trauma any less painful for them.

Embracing this understanding has helped me replace feeling separate with a strong sense of empathy for those who suffer, which in turn creates greater connection. And in that way, we all benefit.

Then there's the issue of time.

Returning to Van der Kolk’s quote once more:

“The nature of trauma is that you have no recollection of it as a story. The nature of traumatic experience is that the brain doesn’t allow a story to be created.”

When attempting to reassemble traumatic moments, to recreate the story of what happened, the predictability of time sometimes falls away. This is something I experienced firsthand during the greatest tragedy of my life, my son Eric’s sudden passing.

I write about it in my memoir, The Full Catastrophe: A Love Story, this way:

We like to think that things happen sequentially, that if we could just gather together the witnesses, a reasonably reliable recreation of the events of a day, of an hour, could be assembled. But time is a funny thing. It moves along, teases us with notions of its constancy, lulls us into believing in its unchangeable properties. Then comes a day when it takes a break, when no amount of recounting of events can bring order to what has happened.

I was in a rush that morning. I broke with routine. Get to the school, get back home. Get Kyle off to work. Get dinner ready; the guests will be waiting. Get on the computer. Get myself back together. I put aside the predictable steps that typically dictate my days. Maybe I dressed before doing my hair. Maybe the jewelry went on first instead of last. I don’t really remember, and why would I? Such inconsequential, fleeting details. Meaningless, really.

But I do remember one thing: In my hurry, I forgot to wear my watch.

In later years, I would come to think of this as the day there was no time.

So for this reason, or perhaps for no reason at all, no matter how I try, I can’t put a sequence to the events of that afternoon. Everything I said was the first thing I said. Everything I thought, I thought the moment I heard.

Finally, a question from Dani’s website:

“What makes us who we are? What combination of memory, history, biology, experience, and that ineffable thing called the soul defines us?”

Good questions, all. Each of these things work synergistically with the others, and together they wield enormous influence over us.

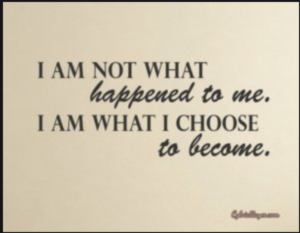

It’s a fine balance, though, working through trauma in all of the ways Van der Kolk describes–addressing the physiological and emotional effects of events that have changed our brains and bodies without our permission, often without our knowledge, things language alone can’t access–without allowing these things to define us.

I fought this following the death of my parents and brother, but I didn’t fully understand it until my son died, and I came face to face with what I knew was an important decision. Again, from The Full Catastrophe:

Eric’s death is something that has happened to me, an overwhelming grief, but it is not my identity. I refuse to let “mother of the boy who died” become all that I am.

There are effects of early trauma that will be part of me as long as I live. Forever I’ll balance the pain of loss, which is as real to me today as it ever was, with gratitude for the equally real joy in my life now.

No doubt our history and biology play huge roles in who we become. Memory and experience–not the same–work in tandem to help us create our own stories about ourselves and our relationship to others.

In no way do I intend to minimize the significant lifelong psychological and physiological impact of trauma. Yet changing the stories we tell ourselves is a key step in moving into a healthier life. As the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl writes in his landmark book, Man’s Search for Meaning, “When we are unable to change our circumstances, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

I’ve come to believe the thing that most defines us in the wake of trauma, as we move through time and work to reframe our memories, comes down to this one key factor.

In the immortal words of Carl Jung, another renowned psychiatrist:

“I am not what happened to me. I am what I choose to become.

Wishing my son, Eric, who would be 42 today, a happy heavenly birthday. For us, he will be forever 20…and 15 (as I think he was here), and 10, and 3. And a newborn, the one who made me a mother.

He lit up the world for us while he was here, and he continues to cheer me on from the other side. Of this I am certain. ♥️

This is beautiful, Casey, and I love the excerpts from your memoir. I’m sure Eric is smiling down on you today, saying “Thanks, Mom, for the memories.”

Thanks so much, Karen, and thanks, as always for reading and sharing!

Lovely writing, Casey.

Thanks so much, Eileen.